模具所有權與 IP 保護:工廠控制如何成為供應商綁架的槓桿

When a factory accepts your first custom 3C electronics order—whether it's a power bank, Bluetooth speaker, or USB drive—the conversation focuses entirely on price, MOQ, and delivery timeline. The mold itself is treated as a technical detail, a necessary cost buried in the overall quotation. This is precisely where the decision-making process starts to diverge from what enterprises assume will happen.

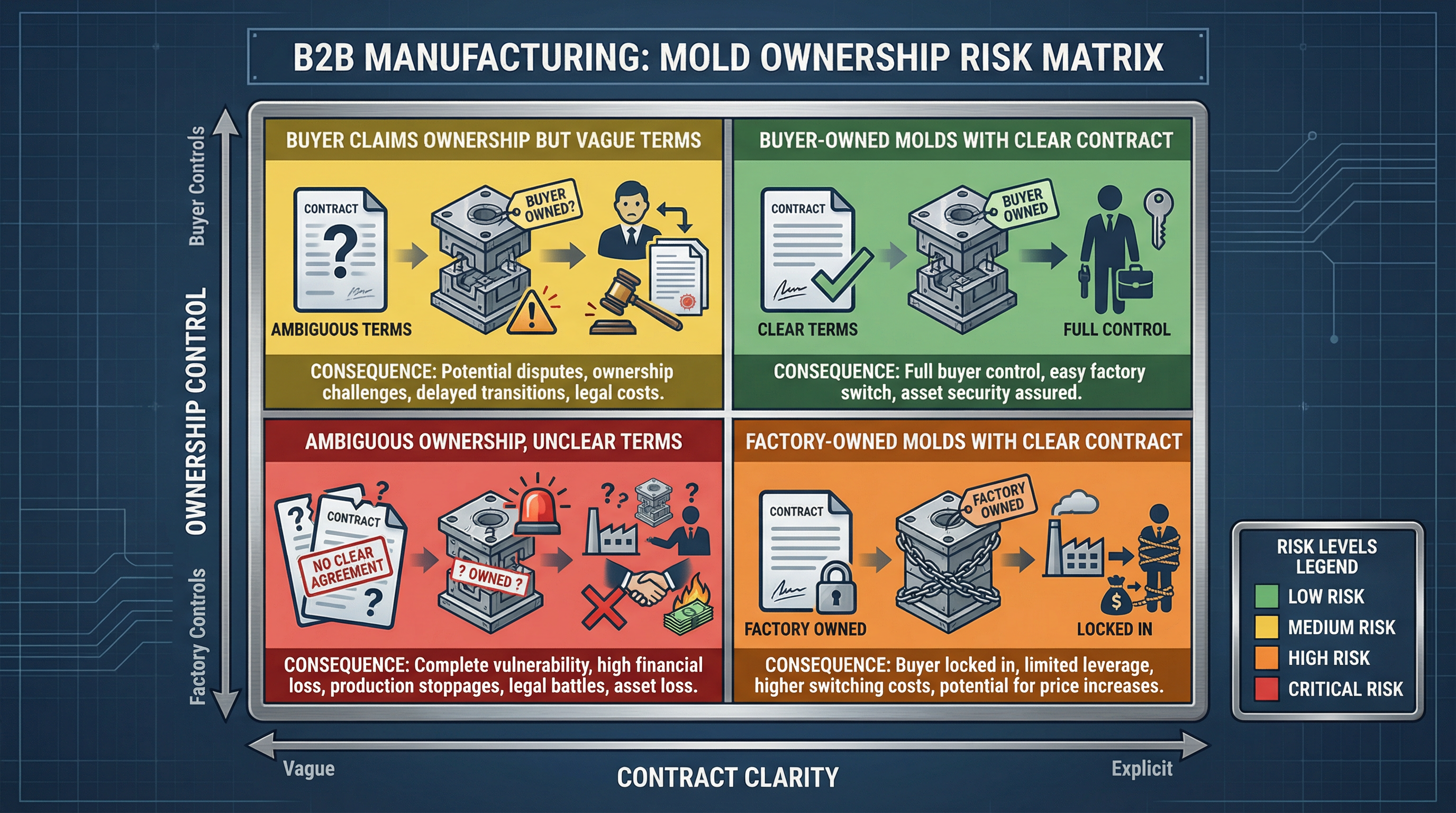

The assumption is straightforward: we pay for the mold development, therefore we own it. In practice, this ownership claim often exists only in the buyer's mind. The factory has no incentive to clarify this ambiguity during the sales phase, and many procurement teams never think to ask. By the time the relationship deteriorates or a price dispute emerges, the question of who actually controls the mold becomes the leverage point that determines whether you can walk away or whether you are locked in.

From a factory perspective, mold control is the single most effective mechanism for retaining customer relationships—or more accurately, for preventing customers from leaving. A factory that holds the molds has structural leverage that transcends price negotiations. If your production line depends on a mold that only the factory possesses, you cannot credibly threaten to move production elsewhere. The factory knows this. The buyer often discovers this only after the first successful production run, when the factory announces a price increase or when quality issues force consideration of alternative suppliers.

The mechanism is subtle but powerful. During initial negotiations, the factory quotes a mold cost as part of the overall project budget. The buyer pays this cost and assumes ownership. But the contract language—if it exists at all—may state that the factory "maintains custody" of the mold during production, or that the mold is "held in trust" for the buyer's benefit. These formulations are intentionally vague. They allow the factory to argue, months or years later, that the mold was never formally transferred to the buyer, that it remains factory property, or that transferring it would violate some unstated agreement. In jurisdictions with weak contract enforcement or where manufacturing disputes are common, this ambiguity becomes a permanent structural advantage for the factory.

Consider the practical sequence. Your enterprise places an initial order for 50,000 custom power banks. The factory develops the mold, produces the first batch successfully, and you begin selling the product. Six months later, demand exceeds expectations and you need to place a follow-up order for 100,000 units. The factory quotes a price 25–30% higher than the original unit cost. When you push back, the factory explains that material costs have risen, labor costs have increased, and the mold requires maintenance. More importantly, the factory suggests that if you are unhappy with the pricing, you are welcome to find another supplier—but the mold will remain with the factory for "safekeeping" until all outstanding obligations are settled. This is not a threat stated explicitly; it is simply a statement of fact about how the relationship works.

At this point, you face a genuine constraint. Moving production to a second factory requires either convincing the first factory to release the mold—which now involves negotiation from a position of weakness—or developing an entirely new mold at the second factory, which means absorbing the full mold cost again. The second factory will also want to develop its own mold rather than use one created by a competitor, both for quality control reasons and because it creates the same structural lock-in. The economic reality is that you cannot afford to abandon the first mold. The factory knows this. The price increase is not a negotiation; it is a statement of the new terms under which the relationship will continue.

This dynamic becomes more acute in custom 3C electronics manufacturing because the mold often embodies the entire intellectual property of the product. A custom power bank's external enclosure, the specific connector placement, the button configuration, the overall form factor—these design elements are captured in the mold itself. If the factory controls the mold, the factory effectively controls the product design. The factory can argue that the design is proprietary to the factory, that the buyer has no right to transfer it, or that doing so would violate intellectual property principles. Whether these arguments are legally sound depends on the jurisdiction and the contract language, but the factory's possession of the physical mold gives it credibility in making these claims.

The IP dimension adds another layer of complexity. In many OEM/ODM relationships, the buyer provides design specifications and the factory executes the manufacturing. The buyer assumes that providing the specifications means retaining ownership of the resulting product design. But if the mold is the embodiment of that design, and if the factory controls the mold, then the factory has a plausible claim to control the design as well. This is especially true if the factory made any modifications to the design during the mold development process—which is common, as factories often adjust designs for manufacturability. The factory can argue that these modifications represent factory IP and therefore the factory has a stake in the mold ownership.

The consequences of this ambiguity extend beyond pricing. If you decide to move production to a second factory and the first factory refuses to release the mold, you have limited options. You can pursue legal action, but this is expensive, time-consuming, and uncertain in outcome, especially if the manufacturing relationship involved a factory in a jurisdiction with different IP standards or contract enforcement mechanisms. You can attempt to recreate the mold from scratch, but this requires reverse-engineering the product, developing new specifications, and absorbing the full mold cost again—often 10,000–50,000 USD for complex custom electronics. You can attempt to negotiate a release, but you are now negotiating from a position of complete weakness; the factory knows you have no alternatives. Or you can accept the new pricing terms and continue the relationship on the factory's terms.

The decision-making blind spot is that enterprises often treat mold ownership as a technical or accounting matter rather than as a strategic control point. During the initial procurement process, the focus is on unit cost, delivery timeline, and quality specifications. The mold cost is simply one line item in the overall budget. The question of who owns the mold after payment is rarely asked, and when it is asked, the factory's response is often reassuring but vague: "Of course, the mold is yours. We are just holding it for you during production." This statement is technically true but operationally misleading. The factory is holding the mold, and in practice, the factory's possession is nine-tenths of the law.

The issue becomes more pronounced when the buyer is managing multiple suppliers or multiple product lines. If you are ordering custom USB drives from one factory, Bluetooth speakers from another, and charging stations from a third, the mold ownership question becomes a portfolio-level risk. Each factory has structural leverage over its portion of your supply chain. If any one factory raises prices or reduces quality, you cannot easily shift production because you do not control the molds. The cumulative effect is that your entire custom electronics supply chain becomes dependent on the goodwill and pricing discipline of multiple factories, none of whom have any incentive to maintain competitive pricing once the molds are in their possession.

The practical solution requires explicit contract language that addresses mold ownership, mold transfer rights, and IP ownership of the mold design. The contract should state clearly that the buyer owns the mold outright, that the factory is merely the custodian during production, and that the buyer has the right to transfer the mold to another factory at any time. The contract should also specify what happens to the mold if the relationship ends: does the factory return the physical mold, provide CAD files and 3D models, or both? What are the costs associated with mold transfer? Who bears the cost of mold maintenance or repair? These details are not negotiated after the relationship deteriorates; they are negotiated upfront, when both parties are motivated to reach agreement.

The challenge is that factories resist this clarity. From the factory's perspective, mold control is the primary mechanism for customer retention. A factory that agrees to explicit buyer ownership and unrestricted transfer rights has surrendered its structural leverage. The factory will argue that it needs to maintain control over the mold to ensure quality, to protect its own IP investments, or to manage the mold's lifecycle. These arguments have some merit, but they also reflect the factory's desire to maintain lock-in. Negotiating this point requires procurement teams to recognize that mold ownership is not a technical detail but a strategic decision variable that determines the entire power dynamic of the supplier relationship.

In the context of custom 3C product procurement for Hong Kong enterprises, this issue is particularly acute because many manufacturing relationships involve factories in mainland China or Southeast Asia, where contract enforcement is less predictable and where the factory's physical possession of the mold creates a significant practical advantage. The factory knows that pursuing legal action across borders is expensive and uncertain. The buyer knows that the factory knows this. The result is that mold ownership disputes often resolve in favor of the factory, not because the factory has a stronger legal claim, but because the buyer's alternatives are so costly.

The relationship between mold ownership and the broader procurement decision framework becomes clear when you recognize that mold control is a form of hidden cost. It is not a line item in the initial quotation, but it is a cost that manifests as reduced pricing flexibility, reduced supplier optionality, and reduced ability to respond to market changes. An enterprise that fails to secure clear mold ownership is effectively accepting a long-term price premium for the convenience of not negotiating this issue upfront. This premium compounds over time, especially if the product is successful and requires multiple production runs or volume increases.

The decision to prioritize mold ownership clarity is therefore not a legal nicety; it is a procurement decision with direct financial implications. It determines whether you can maintain competitive pressure on your supplier, whether you can respond to quality issues by switching factories, and whether you retain strategic flexibility as market conditions change. This is why the question of mold ownership should be addressed at the same level of priority as MOQ, unit cost, and delivery timeline—not as an afterthought once the relationship is already established.