樣品簽核為何無法保證量產品質:客製化 3C 產品確認流程的隱藏陷阱

When a procurement manager signs off on a sample for custom 3C products, they often believe the hard part is done. The design is approved, the materials are confirmed, and the supplier has demonstrated they can execute. Yet within weeks of production launch, quality complaints flood in—color inconsistencies, adhesive failures, dimensional drift, or structural weaknesses that were never present in the approved sample. This is not a rare edge case; it is perhaps the most predictable failure mode in B2B custom manufacturing, and it stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what "sample approval" actually means.

The gap between sample and production quality is rarely accidental. It is the result of systematic cost pressures, process shortcuts, and material substitutions that occur once the buyer's attention shifts away from the factory floor. What makes this particularly insidious is that the supplier is often not being deliberately deceptive—they are simply responding to the economic incentives embedded in the contract and the production schedule. If the contract does not explicitly forbid material downgrading, if the process parameters are not locked in writing, if no one is monitoring the factory during production, then the supplier has every reason to optimize for speed and margin rather than consistency.

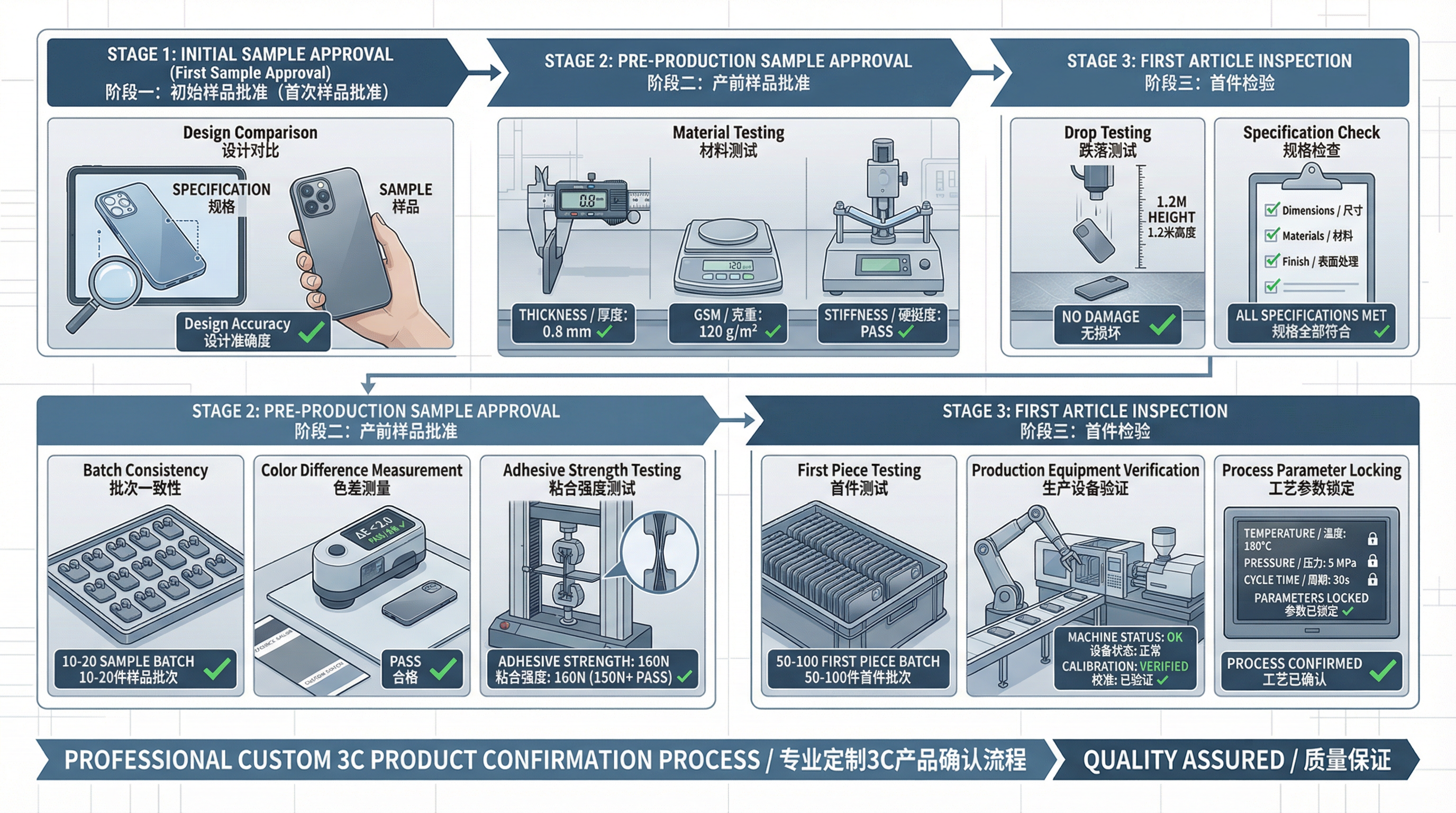

The real problem lies in how procurement teams approach sample confirmation itself. Most treat it as a binary gate: either the sample passes or it fails. In reality, sample confirmation is a three-stage verification process, each with distinct objectives and risk profiles. Skipping or abbreviating any of these stages creates blind spots that will manifest as quality failures downstream.

The Three Stages of Sample Confirmation

The first stage is initial sample approval, where the focus is purely on design translation and material selection. At this point, the supplier is typically using their best materials, their most experienced craftspeople, and their most precise equipment—because they are trying to prove they understand the brief. The procurement team should be comparing the physical sample against the design specification, checking dimensions, color accuracy, surface finish, and material properties. This is where you verify that the supplier can even execute the design as intended. If the initial sample fails here, there is no point proceeding further. But if it passes, you have only confirmed one thing: the supplier can make it correctly. You have not yet confirmed they will make it consistently at scale.

The second stage is pre-production sample approval, and this is where most procurement teams falter. Instead of requesting a single perfect sample, you should demand 10 to 20 samples produced using the actual production line and process. These samples should be subjected to batch consistency testing—measuring color variation across the batch using a spectrophotometer, testing adhesive strength on multiple units, running drop tests from standard heights, checking dimensional consistency. The goal is not perfection; it is to verify that the supplier's process is stable enough to produce consistent results across a batch. If three out of twenty samples fail adhesive testing, or if color variation exceeds acceptable limits, the process is not ready for mass production. Returning to this stage and demanding process refinement is far cheaper than discovering the problem after 50,000 units have been manufactured.

The third stage is first article inspection, conducted at the actual production facility once the tooling is installed and the production line is running. This is where you lock in the process parameters. You should be present (or have a quality representative present) to observe the production setup, verify that the equipment is calibrated correctly, and inspect the first 50 to 100 pieces coming off the line. These pieces should meet the same standards as the pre-production samples. Once they do, you document every process parameter—printing pressure, adhesive application rate, curing temperature, curing time, assembly sequence—and require the supplier to maintain these settings for the entire production run. Any deviation requires written approval. This is not bureaucratic overkill; it is the only mechanism that prevents the supplier from "optimizing" the process in ways that degrade quality.

Why the Gap Emerges

The five most common reasons for sample-to-production quality degradation are material substitution, process simplification, equipment differences, workforce changes, and schedule pressure. Understanding each one is essential for building preventive controls into your contract and monitoring protocols.

Material substitution is the most frequent culprit. The sample uses aerospace-grade aluminum or virgin polymers; production switches to recycled alloys or industrial-grade materials to reduce cost. The sample uses premium adhesives; production uses cheaper alternatives that cure faster but have lower shear strength. The sample uses hand-finished components; production uses automated stamping that introduces micro-burrs. None of these changes are visible in casual inspection, but they compound into measurable performance degradation. The preventive measure is explicit: specify material brands and grades in the contract, not just generic categories. Request material certificates of analysis for each production batch. Conduct periodic material audits at the supplier's facility.

Process simplification occurs because production efficiency and sample perfection are often in direct conflict. The sample might involve ten assembly steps, including hand-finishing and multiple quality gates. Production streamlines this to five steps, eliminating the hand-finishing and consolidating quality checks. The result is faster throughput but lower consistency. The preventive measure is to document the exact process flow used to create the approved sample, including all intermediate steps and quality gates. Require written approval before any process step is eliminated or consolidated. Conduct process audits during production to verify adherence.

Equipment differences arise because the sample is often produced on the supplier's best equipment—precision CNC machines, calibrated assembly fixtures, specialized tooling. Mass production might use older, more general-purpose equipment with looser tolerances. A sample produced on a micron-precision lathe might have surface finishes that cannot be replicated on a standard mill. The preventive measure is to require that pre-production samples be made on the same equipment that will be used for mass production. Verify equipment specifications and calibration records. Conduct equipment audits before production begins.

Workforce changes are subtle but significant. The sample is often made by the supplier's most experienced technicians—master craftspeople who understand the nuances of the product. Mass production relies on general labor, often with high turnover and minimal training. A skilled operator might know to adjust curing time based on ambient humidity; a general laborer follows a fixed schedule regardless of conditions. The preventive measure is to require operator training and certification. Conduct periodic audits of workforce qualifications. Include quality incentives in the supplier contract to encourage retention of skilled workers.

Schedule pressure is perhaps the most insidious factor. When production deadlines tighten, suppliers face a choice: maintain quality standards and miss the deadline, or cut corners and meet the schedule. Most choose the latter. Curing times are shortened, quality inspections are abbreviated, material testing is skipped. The preventive measure is to build realistic production timelines into your contracts, with penalty clauses for quality failures that exceed schedule bonuses for on-time delivery. Communicate clearly that quality is non-negotiable, even if it means pushing the delivery date.

The Real Cost of Inadequate Sample Confirmation

Consider a real scenario: a Hong Kong technology company orders 100,000 custom USB enclosures for a major client. The sample is perfect—precise dimensions, flawless finish, excellent build quality. The supplier quotes a competitive price and promises a 12-week lead time. The procurement manager approves the sample and places the order.

Eight weeks into production, the first container arrives. The buyer's quality team opens a random box and immediately spots problems: color variation across units, adhesive seeping from joints, dimensional drift in connector alignment. A full inspection of 500 units reveals a 12% defect rate. The buyer has a choice: accept the shipment and risk customer complaints, or reject it and face a six-week delay while the supplier reworks the batch. Either way, the buyer loses. The supplier claims they followed the approved sample, but the buyer never verified that the production process was stable or that materials were consistent. The contract is ambiguous about who bears the cost of rework.

This scenario is not hypothetical. It plays out dozens of times per year in the custom manufacturing ecosystem. The cost is not just the rework—it is the damaged customer relationship, the lost market window, the internal crisis management, the legal disputes over responsibility. All of this could have been prevented by a rigorous three-stage sample confirmation process and explicit contractual controls.

Building Effective Sample Confirmation into Your Procurement Process

The first step is to reframe sample confirmation in your mind: it is not a gate, it is a process. It requires time, resources, and technical expertise. If your procurement team is treating sample approval as a 30-minute review, you are setting yourself up for failure.

The second step is to document your expectations clearly in the contract. Specify the number of samples required at each stage, the testing methods and acceptance criteria, the process parameters that must be locked in, and the consequences of deviation. Include a clause requiring the supplier to maintain material batch traceability and to provide certificates of analysis for critical materials. Require written approval before any material, process, or equipment change.

The third step is to invest in on-site quality oversight. For large orders (50,000+ units), consider stationing a quality representative at the supplier's facility for the duration of production. This person should conduct first-middle-last inspections throughout the production run, verify process parameter compliance, and have authority to halt production if standards are not being met. This is expensive, but it is far cheaper than discovering problems after shipment.

The fourth step is to build feedback loops into your supplier relationships. After each production run, conduct a post-delivery quality review with the supplier. Document any issues, their root causes, and the corrective actions taken. Use this data to refine your sample confirmation process for future orders. Suppliers who consistently deliver quality improvements should be rewarded with higher order volumes and better payment terms. Those who cut corners should face penalties or be replaced.

The fifth step is to recognize that sample confirmation is not a one-time event—it is an ongoing commitment. Even after production begins, continue to monitor quality through periodic audits and testing. If you detect drift in any dimension—color, dimensional accuracy, adhesive strength—escalate immediately and require the supplier to investigate and correct. Do not wait until the entire batch is complete to discover problems.

Connecting to Your Broader Procurement Strategy

Sample confirmation sits at a critical juncture in the procurement process. It is where design intent meets manufacturing reality, where theoretical specifications become physical products, where the supplier's true capabilities are revealed. Getting this step right is foundational to everything that follows—cost control, schedule reliability, customer satisfaction, and long-term supplier relationships. When procurement teams rush through sample confirmation or treat it as a formality, they are essentially betting that the supplier will maintain quality standards without oversight or incentive. History suggests this is a losing bet.

The most successful procurement organizations treat sample confirmation as a core competency, not an administrative task. They invest in technical expertise, they build rigorous processes, they maintain clear contractual controls, and they stay engaged throughout production. For custom 3C products—where quality directly impacts brand reputation and customer experience—this investment is not optional. It is the difference between a supplier relationship that delivers consistent value and one that becomes a source of recurring problems.